Mesa Verde, A Civilization on the Edge

What would induce you to live on a cliff, like the Mesa Verde cliffdwellers did?

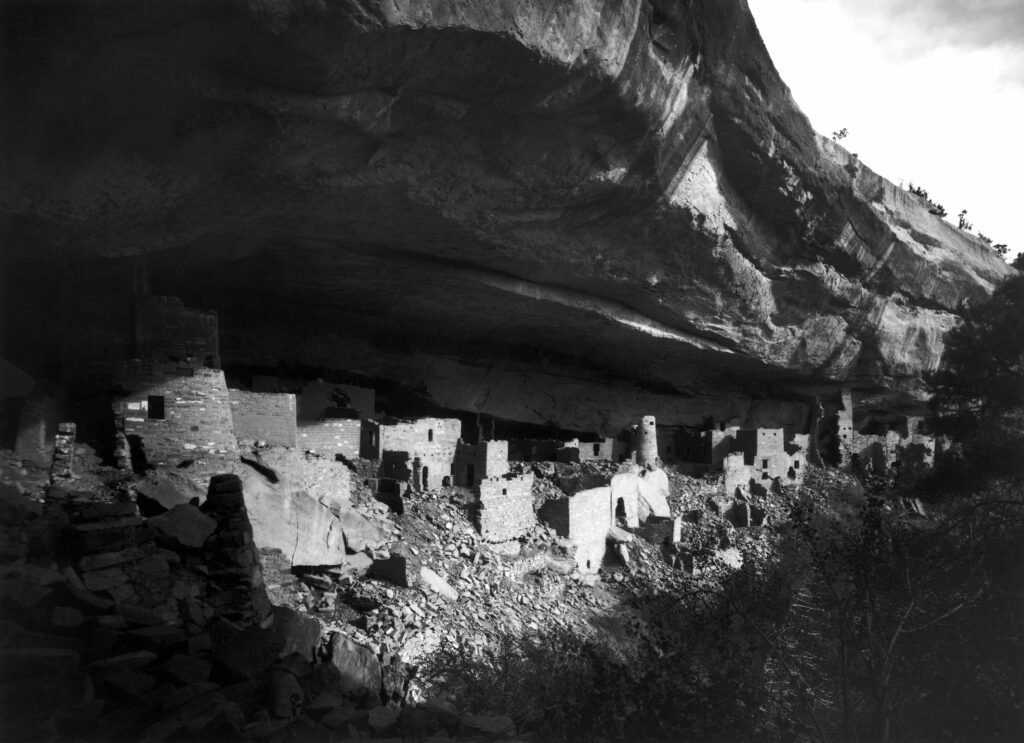

I’m talking a 600ft drop on one side, and rise of 50-100ft above you. Your family lives in a crack in the stone face, with no water source and no room for a garden. To reach your home, you have to climb up the cliff on handholds carved into the rock, and walk along the edge of a precipice through places where the stone sags down from above so low that you are forced to crawl. One false move, and you plummet to your death.

The view, however, is to die for.

I’m going to tell you a story.

It’s been gleaned from dozens of sources, and—fair warning—is actually just an archeologists’ best guess. But barring an actual written record of what occurred so long ago, this is probably the closest to the truth that we can get.

Our story starts with the weather. Fascinating, right?

Around 950BC the earth, for reasons of… well, God’s, we must assume, entered a period of we call the Medieval Warm Period. It brought an era of lush growth to the American Southwest and witnessed the rise of a kingdom (or kingdoms) in the Four Corners region where Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and Colorado meet. This kingdom built hundreds of miles of roads, some of them as stubbornly straight as those the Romans built a thousand years before, and grand palaces three to five stories high with 700+ rooms. Not built on cliffs, but on the relatively fertile bottom land. They made signal towers, Lord of the Rings style, to flash warnings from one end of their domain to another, and ushered in an era of peace between the different pueblos.

The center of this kingdom or city-state began in Mesa Verde (but don’tthink of the photos you’ve seen of the Cliff Palace—that came later.) Later, the capital was moved to Chaco Canyon, some 150 miles south.

There are several palaces, or Great Houses, in Chaco Canyon. The biggest have hundreds of rooms, granaries, kivas (at this point in history a kiva was an underground living room, cool in the summer and warm in the winter, where family groups gathered,) and what appears to be a paved ball court. Into these Great Houses flowed turquoise from Nevada, California and Colorado, copper, cocoa and macaws from Mexico, shells from the coast, and corn from the entire surrounding area.

The elite buried in the great houses were better off than their neighbors. Dr. Stephen H. Lekson says “Great House people were bigger and healthier, and had a great many fancy things that other people did not have. The men were buff with big muscles, the women did not work: No squatting facets, no corn grinding.” They may have come down from the North, as some legends tell, or up from Mexico. Or they could have risen up from among the local tribes.

They (or—ahem!—the regular folk who worked for them,) built an extensive system of canals and dams to catch all available rainwater, and for a time, the land prospered.

It was a time of prosperity and peace. Well, except for the occasional “extreme processing events.” That’s what archeologists call it when a family was killed, the remains were dismembered and eaten, and the house was burnt. But don’t worry, apparently it was no big deal. The neighbors went on with life as usual. No one looted, no one bothered to bury the bodies. It was just ignored, leading archeologists to assume that it was just a government-sanctioned execution. And it wasn’t that common, either. Well, not at first.

Originally, the massive palaces and surrounding villages were built using timber beams from the Ponderosa pine forests that filled the region, but as the area became deforested, lumber had to be brought in from the mountains, a trek of more than fifty miles.

Time passed. A drought came, but the imports into Chaco canyon continued. More corn. More turquoise. “Black drink” from the Mississippian culture far to the north, and cocoa dribbled into bowls on the ground by a man standing on a high ladder, giving it a creamy, frothy texture. A new kind of pottery appeared, one that took, yes, lots and lots of wood carted in from the distant mountains by people whose skeletons show the strain of prolonged burden bearing, but you see, this pottery was red. San Juan Red Wares, we call it. Very fancy. It seems to have been all the rage.

And before too long, the women in the houses of the Chaco elite outnumbered the men by over four to one. Odd, eh? Some have suggested that the missing male population can be found among the scattered executions, where the dead are mostly males and small children.

The first real drought of the period began in 1130, and that’s when we think the elites began to squabble. The level of violence increased, and not just in the houses of the common people. Perhaps two heirs, competing for power, dragged to rest of the nobles into factions, or maybe it was due to the shift in religion from venerating the moon to worshiping the sun, but warfare broke out on a larger scale.

Some of the elite moved to a place we call Aztec Ruin, 55 miles south, where they copy + pasted their capital city. Archeologist Craig Childs said, “Aztec’s great houses mirror those of Downtown Chaco. They were designed to match Chaco down to the exact square footage, angled toward and away from one another in the same fashion as Chaco’s great houses, even elevated around one another in a similar way… This was an almost exact duplication.”

No matter the cause of the move, it didn’t work. The drought continued. The violence escalated. People attacked even the graves of their enemies’ families, desecrating them.

By the time the drought ended, the divide between the warring parties was too great. The common people began building their houses back-to-back in defensive attitudes, clumping together in ever-greater numbers. Defensive walls went up. With each decade, the death toll increased. Some people took to living in the cliffs, traveling back and forth to the more habitable areas to farm, where according to one legend “the hollows of the rocks were filled with blood.”

Things got really nasty. Victors cannibalized the dead, waited an appropriate period, and then carefully desecrated their victim’s hearthstones by depositing the last of the enemy remains there in the form of a coprolite.

I think I’d head to the cliffs too.

The beautiful Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde was built between 1200 and 1275. Take a fresh look at this place.

Isn’t it peaceful looking? So lovely, exotic and ancient! Of course… you’ll need to climb ladders to get there if you want to visit. Almost like the builders chose that beautiful spot out of, well, fear for their lives. Location, location, location.

And then, in the last decade of the thirteenth century, something happened.

The survivors fled. They left behind cups hanging on pegs, pottery, corncobs in granaries, clothes… even a ceremonial knife identical to the ones used in Maya temples to remove the hearts from human sacrifices.

We don’t know why they left, but there is a very old legend about a time of bloodshed and chaos, and the common people who decided that the nightmare of violence needed to end. Enough was enough. Perhaps they rebelled against the remaining elites, or perhaps the last heads of the warring parties killed each other. At any rate, everyone left alive packed up and left, stopping on the way only long enough for an elaborate “ceremony of forgetting.”

One can only speculate that the entire web of belief systems practiced by the Pueblo people centered around “forgetting” stem from this time. They have elaborate ceremonies for leaving “negative” experiences behind, and ensuring the past will never be repeated.

I’m never going to look at the Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde the same way again. What would induce me to live on a cliff? The same thing it took to make them do it. Being faced with the alternative of something far, far more dangerous than heights. And that’s really saying something.

(For an incomplete list of sources, scroll to the bottom of this post. And if you’re at all interested in some crazy history, you should probably look up the podcast The American Southwest by Thomas Wayne Riley.)

Sources:

The Archaeology of Yellow Jacket Pueblo: Excavations at a Large Community Center in Southwestern Colorado Edited by Kristin A. Kuckelman. The Crow Canyon Archaeological Center.

Anasazi Mummified Some of Their Dead, Anthropologist Contends by Lee Siegel on April 5, 1998.

Cannibals of the Canyon by Douglas Preston, The New Yorker, November 30, 1998.

Prehistoric Warfare in the American Southwest by Steven A Leblanc.

The Lost world of the Old Ones by David Roberts.

In Search of the Old Ones: Exploring the Anasazi World of the Southwest by David Roberts.

Behind the Bears Ears: Exploring the Cultural and Natural Histories of a Sacred Landscape.

Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest by Stephen Plog.

A Study of Southwestern Archaeology by Stephen Lekson.

Tracing Time: Seasons of Rock Art on the Colorado Plateau by Craig Childs.

House of Rain: Tracing a Vanished Civilization Across the American Southwest by Craig Childs